How to Murder a Movie I

Sometimes I wonder if I’ve made a mistake. For example, today, I’m stuck in the daily slow-moving traffic of Los Angeles, it’s hot, the air in the car is stuffy, and my trench coat is practically sticking to me.

Many drivers rolling slowly past me look at my car with great astonishment. It’s an old model, built in 1973, the paint is cracked, there are a few dents, and the car is covered in dust.

But that’s not why people are looking; it’s the blue light on the roof of my car and the lettering on the doors: Hollywood Police, Movie Murder Department.

I begged them for a newer car with air conditioning, but the chief refused. Not authentic enough, he said, not interesting enough for Hollywood. The people of Hollywood demand a special inspector, an original, someone extraordinary. They want an inspector they know from television.

And so I sit here in my car without air conditioning, in an old trench coat, with a cigar between my lips, waiting for my next assignment. Life in the police force isn’t easy: long hours on duty, bloody crime scenes, unreliable witnesses.

Maybe it would be easier for me if I were really a police officer, but I’m just an actor who took on this job last year.

Ted, the real inspector, has been transferred to desk duty; he’s the one who actually solves our cases. It may sound unbelievable, but this is Hollywood. All the Hollywood stars who had dealings with him were disappointed. Average looks, no peculiarities, no quirky details.

“This is supposed to be an inspector?” they complained to the governor.

So they hired me. The whole act, you know, old car, trench coat, cigar, a special accent, and all those peculiar gestures and the way I walk. Plus my trademark, my three famous lines: I’m a detective, I’m allowed to do that. My brother’s in the Navy. Do you have that with mustard too?

People like that, Hollywood stars like that.

You can do it, the chief told me when he handed me my badge last year. You’re taking on a responsible job here in the Movie Murder Department. It’s our job to find out why movies are killed. We’re talking about greed, gigantic egos, criminal energy, and tax evasion. And that’s just the producer. As for the director and the actors, there are real abysses there.

But enough of that. Put on your trench coat, practice your famous lines, and work on your gestures. That’s the only way we can impress the Hollywood stars.

Remember, it’s like in the movies. It’s not about reality, it’s just about how good it looks.

And so I sit here in my old car, next to me the cameraman who will film the new case, and we wait. The radio plays the same endless royalty-free music that we are allowed to use for free. In the back seat is a stack of authentic-looking newspapers with only the front page printed. The only thing that’s real here is the heat and the smell of old socks.

Finally, a message comes over the police radio. The cameraman shoulders the camera and nods to me. It’s time. The message is short and bloody. A new case, a brutally murdered film. Time for my big moment. I turn around in the moving traffic.

A driver honks his horn indignantly and starts swearing. I roll down the side window. “I’m allowed to do this, I’m an inspector,” I shout at him and speed off with screeching tires. Good work by the design team, they’ve finally managed to create an authentic tire squeal.

Less than three cuts later, I arrive at the villa. A typical Hollywood villa, tasteless, expensive, and with half-dried palm trees in the driveway. On the lawn is a fountain with golden water and red plastic roses.

In front of the door is a nervous public relations manager, skinny, pale, with a cell phone and sunglasses.

“I’m sorry, you can’t come in like that,” he says, “and smoking is strictly prohibited here.”

“I’m an inspector, I’m allowed to do that,” I say, “and this isn’t a real cigar, it’s just a movie prop.”

Ignoring him, I walk past him and enter the villa. The police officer in the foyer leads me into a large study. A group of people has gathered in the room. The usual scene: police officers, witnesses, crime scene specialists. In the background, a fake fireplace in which important documents and forged tax receipts are burning. Hollywood.

My cameraman pans the camera towards me and prepares everything for a close-up.

“My name is Garrett, Hollywood Police, Movie Murder Department,” I introduce myself.

“You reported a movie murder?”

Gillbert, our makeup specialist, replies, “Yes, the murder victim is over there, in the set next door.”

In the set next door? I take a closer look around. The room is an absurd mixture of expensive furnishings and cheap walls. It looks like a movie set.

“This isn’t a mansion?” I ask incredulously, “This is all just a set?”

One of the producers nods. “Yes, that’s right, we moved out of our mansion for tax reasons and now live on the film set.

Every expense can be deducted with this system. You understand. It’s the ideal solution. Why should I drink coffee in my house and pay for it myself when I can write off the same coffee here as a budget item?

How about you, Inspector? Would you like anything? Coffee, a little refreshment, a massage? We have everything available. I can recommend our breakfast. A croissant fresh from the oven with some local organic honey. “

”Do you have that with mustard too?“ I ask.

”With mustard, no.“

”Then no.“

”We should go to the crime scene now,“ suggests my cameraman.

”Agreed.”

The sight in the next room makes me shudder. In all my years as a movie murder inspector, I have never seen such a horrific crime scene.

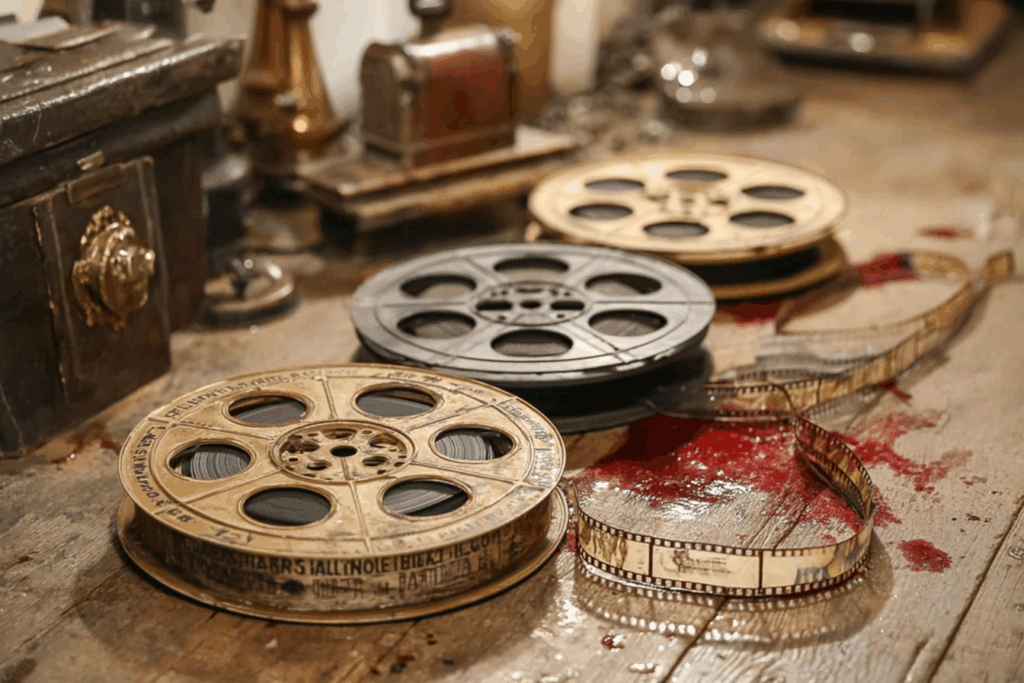

Several film reels lie side by side on the floor, some of the tapes have been pulled out and are curled up on the floor. In between them are several red stains. Raspberry jam. I look at some of the footage. Underexposed, poor framing, no color correction. This is no simple film murder, this is a massacre!

Shaken, I stand up. What goes on in some people’s minds that they are capable of such crimes? Innocent film reels hoping for a big Hollywood career, and then this. I will find the perpetrator, I swear to myself. Even if it takes the entire television season this year.

Kovalsksi, who never gets a leading role because of his complicated name and is always relegated to supporting roles, kneels next to the film reels. With a magnifying glass and a flashlight, he examines the film reels for important clues.

“Can you tell us anything about the time of the crime, Kovalsksi?”

“I can only give a rough estimate at this point, but I think the murder took place between March and October of this year.”

“That helps me a lot,” I say.

“I think I see something,” he says excitedly. He waves the cameraman over and dramatically puts on white gloves. With tweezers, he carefully reaches between the film reels. “Something is stuck in here.”

A dramatic scenario immediately plays out in my head. He’s going to pull a caterpillar out of one of the film reels and show it to me. A caterpillar that will turn into a butterfly. Are we dealing with a crazy serial killer? Is this already the preparation for the next season?

Kovalsksi manages to grasp the object with the tweezers. He carefully pulls the object out.

“What is it?” I ask. “A piece of paper?”

Kovalski pauses dramatically and then looks directly into the camera.

“Not just a piece of paper,” he says. “This little piece of paper is a script. It’s the script for the murdered film.”

A film cut, dramatic music, and I’m back in the study. For the first time, I take a closer look at the witnesses, and what I see is unusual even for Hollywood. Never in my career as an actor or inspector have I seen such an unusual group of suspects. The camera only shows the group briefly; later, during the interrogations, we will see each individual in more detail.

“I could deliver a long monologue now,” I say, “but we are under time pressure. We only have 45 minutes, so there is enough time for the commercial breaks.”

“I will therefore question you individually.” I point to the inconspicuous man on the sofa wearing a golden crown. “I’ll start with you.”